Traslation by Luigina D’Introno

In his studio, Délio Jasse shows the repertoire of colonial-era images he collects as an essential part of his work. In this interview, the artist talks about his approach to photography and his participation in the group exhibition Souvenir d’Italie presented in the OFF section in the occasion of the Dak’Art Contemporary African Art Biennial, ongoing until 7 December.

Where did the idea of the colonial archive come from?

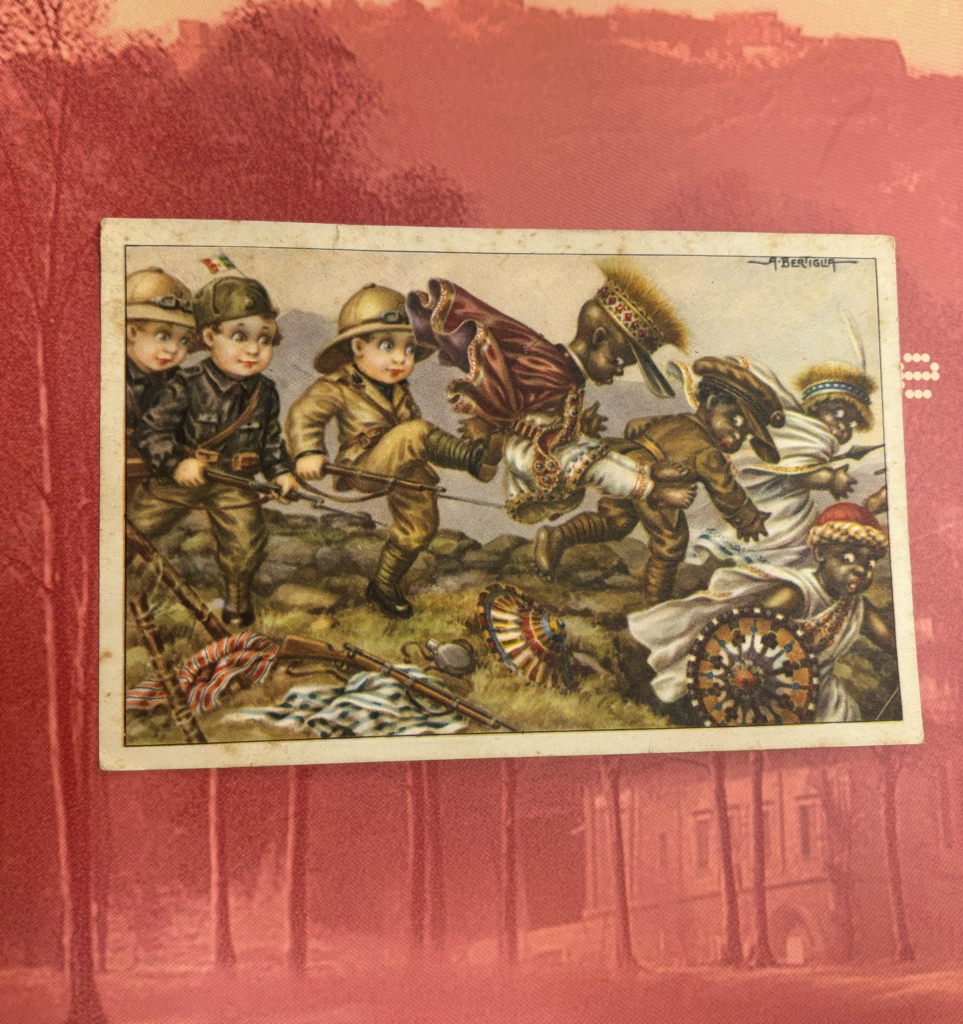

The archive stems from the way stories are told in colonial postcards and photographs. For example, in one postcard the European colonial children kick the black king children. I am very interested in the unofficial archive of people who lived through that period.

From the repertory of Délio Jasse

Do you recount in this way the non-visible opposing narrative?

Exactly. I don’t work with shots taken of black people, which are only produced to sell a type of image in Europe. I am interested in showing what was in the colonisers’ homes, what they did, how they posed in photographs, this world nobody cared about. Nowadays, I highlight another kind of souvenir, almost a parallel and controversial one. Although stereotypical photography still applies today, I pay attention to who has photographed. What we see in exhibitions, newspapers and books is part of a cleaning of the archive, where the product to be sold arrives already prepared and ready to be eaten. Instead, my task is to travel and navigate through a raw, unseen archive. I am not interested in creating photographs or inventing them, my intervention is to take the original and present it, I do not perform a colonial ‘cleaning’, because it must have a sign of that past.

So do you ask those who lived almost unconsciously through that period what actually happened, through their family memory?

One thing is telling an almost invented and readapted story, a lying story. Another thing is the private, vernacular album that tells you something with evidence. On the back you can see who printed it and who took it. In all the colonies there was an official photographer, as Masa Mengiste writes in the book The Shadow King. His point of view is not a western one or an Italian one like Angelo Del Bocca perspective, which, however, was important. We are used to having information from the side of those who colonised, who speak their truth. Here it is a black writer from Eritrea who tells the story.

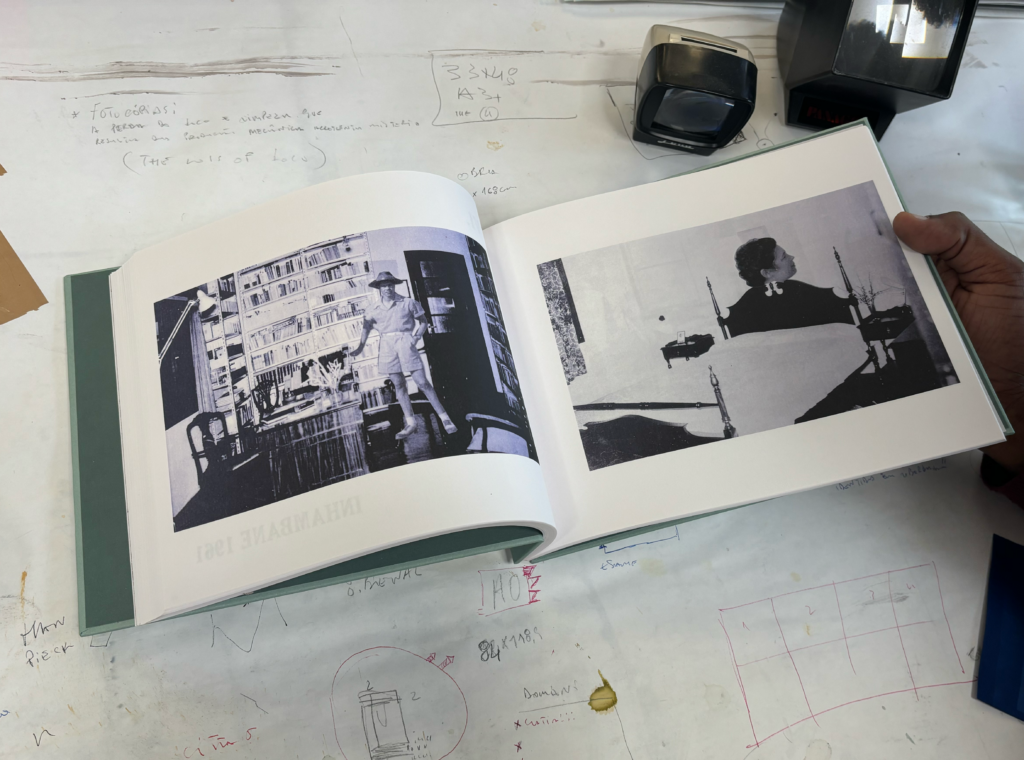

From the repertory of Délio Jasse

In some of the photographs I see in the studio, European children are shown smiling next to freshly killed animals or posing next to a camera to be tested. Black children, on the other hand, are depicted naked, on the ground like animals looking for food. Does photography play a cheating role here?

The manipulation of colonialism is mainly through photography. We find it in the memories and in the writing behind the postcards, e.g. ‘let’s count on seeing panthers otherwise what Africa it is?’. The colonisers are looking at the dead animal. Their expression was angelic saying ‘I did nothing’. In Italy there was this denial of the past. Italians desired to see themselves as good people, when instead they used chemical weapons. Whenever people did not know each other, they killed each other.

Even the geographical names, for example on Italian maps of former colonies, were invented names, they were not based on those that already existed in Africa. Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia maps were produced by inventing colours. Who draws? Who programmes? Who projects? What name do you give?

How does your work fit into these colonial photographs?

It is a game. I play the spectator. What happens is that you recognise certain objects, like a grandmother’s jacket, a chandelier, a car. I am also interested in architecture because it tells you about an era and it reflects the people who built it or took a photograph there. Like two lovers near a fountain who look like they are in Europe, instead they are in Africa because that fountain, that architecture was all reproduced for the colonisers to live in. I create this link between what you recognise and colonialism. Many things are recognisable because Europe has produced similar fascist images. And what the viewer sees as similar to himself enters him and I go to return precisely this comfort from personal memory to collective memory.

Courtesy of the artist Délio Jasse

So, what is the vision that changes in visitors?

My job is to be a mirror and to make people accept the past so that it does not return, even if we see today how they continue to plunder Africa for its raw materials. What happens when I talk about this? When I say “Did you see what Italy did?”, I’m always answered “Well, he didn’t do anything, now there’s China”. It looks like a football match, right? So, we must work on the collective memory, we must discover certain things together.

This attitude was often seen in the visitors during the exhibition Souvenir d’Italie?

There was a spectator who asked me “Why this job? Why did you choose it?”. I said bluntly “Have you seen this space where we are now? It’s a colonial architecture, a very beautiful one; but once you or I as black people could not have stayed here, it was impossible. I could go in only to clean or paint”.

They often ask me how I don’t get angry when I look at these documents and images. I work with everything, but I’m very calm. Obviously in the selection phase I am angry, but I am in the studio where I work as a surgeon. The surgeon doesn’t mind seeing blood, because he is prepared to see it. For me it is the same thing with colonial material.

Délio Jasse, Città Foresta, 2022. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist

In the exhibition at the Tate Modern we were 35 African photographers and the only one who represents white people in photography was me. A friend told me “Why do you only represent white people in your photograph?”, but colonialism was not done by blacks, it has always been caused by whites. Or “how strong is this work of yours!” Who photographed is strong, I’m not. It is also important to ask where these old photographs are located.

They’re not in Africa, they’re in Europe. They made them to show that they brought civilization. There were these photo that have been found and have been sent to the brother of a soldier to develop film. He asked in the letter not to show them to their mother, because there were pictures of naked black women. I made an exhibition with this title. One viewer goes to see the exhibition, wow, don’t tell mama, no? Then when you see the colonial photographs you get kind of a shock.

What are you working on? What are your next projects?

I am preparing an exhibition for March in the Filomena Soares gallery.

I’m printing on the thermal blankets that they put to migrants when they arrive or that are anyway needed for heating or cooling. The stamps I printed above are approval or refusal of passage visas. It is forbidden to enter without this visa. There are 4 in total. Then there will be small backlit image visualizers where the photos go inside and you see a different story. There are fictitious collages where I superimpose real images of environments and people. The history of colonialism is all a European invention. I am telling my story here and creating a new narrative. For example, I insert a lady’s head on the headboard of the bed in the room of the minister of Mozambique (behind the photographs of this official service of the minister’s apartment is written meticulously what rooms are and what we see), or behind a colonial palace I place military planes.

You used colonial language to disassemble their own photographs

Exactly. I play with the viewer in these photographs, like inserting a scout, an explorer into the judge’s office. The titles are also real, I report the official ones. I’m not looking for a new title, but it’s based on the archive and what is already written. I’m also, almost the only photographer who produces all the printing techniques, by working with the archive. Why do I do it? Because with all the technique I dismantle the photograph and I assemble it.

Délio Jasse, Visitate l’Italia, 2022. Courtesy of the artist

Often you work with stamps and documents, related to identity. It is the document that says who you are and not you say. Do you care about this aspect?

I am very interested in the photograph combined with the document, as in the various Portuguese passports of the 50s or someone more recent, which I collect. When I think of the document I immediately think of the passport, the first document we get new often or always. From there you get your name and your date of birth. Then comes the half moon stamp that creates who you are. It is the system that matches and creates your identity. Every time you need to move around the country you need this document. They ask who you are? Why do you enter? So you have to stamp again. If you have to go from Senegal to a country in Europe, it is impossible for you. You have to have a banck account, many documents and face a heavy bureaucracy, while a Westerner even if he has no banck account or anything, can go anywhere. He can stay there three, four or five months. On the contrary, an African arrives by boat then by dinghy or swimming, risking not to enter and end up drowned in the sea because it is illegal for them. But if you have an oil deal or an economic deal, then you can enter. They accept you. Many artists have problems with visas. In a group exhibition I attended they could not come. What you need is this aggressive stamp that says ‘yes you can enter’ or ‘no you cannot’. If he says yes, he stamps and if he says no, he stamps anyway. You also need that stamp or that form to stay in a country, because without it you cannot open a bank account and you cannot travel. It limits you in everything.

Délio Jasse is an artist interested in analog photographic printing processes such as cyanotype and “Van Dyke Brown.” In addition to the development of his own personal printing techniques, Jasse with his meta-photographic approach transforms colonial photography to search for a collective memory and to approach the past consciously. Colonial wounds in his work emerge from the intimate stories of families and individuals who lived through the era. He uses sought-after materials singular to the photographic context, such as textiles, 1950s pedestals and vintage viewers.

He has participated in international exhibitions MAXXI, Rome (2018); Villa Romana, Florence (2018); Image Biennale, Lugano (solo, 2017); Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm (2017); SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin (2017); Bamako Encounters, Bamako (2017); Lagos Biennale, Lagos (2017); Tiwani Contemporary, London (solo, 2016); Walther Collection Project Space, NY (2016); Dak’art Biennale International Exhibition (2016); and the Angola Pavilion, 56th Venice Biennale (2015); Dak’art Biennale International Exhibition (2024).