Traslation by Luigina D’Introno

In a focused and attentive reflection on contemporary art and its post-colonial paradigms, Elvira Vannini, art critic and historian, disseminates an all-feminist, ecological and anti-imperialist art. Through her magazine Hot Potatoes, she formulates a new critique.

In her case, the terms feminism and de-colonialism do not imply a passing fad, but the status of her work. What are the aims of your writing in Hot Potatoes? How did the project come about?

The project was born out of the idea of reclaiming a space for contemporary aesthetic-political critique that would reactivate radical, non-hegemonic counter-historical memories. The feminist perspective became the lens through which observe and interrogate the boundary between the visible and the repressed, to include questions about the art system, its production segments and its ideological-cultural structures. I am an art historian and the paradigm I come from is hierarchical, bourgeois, Eurocentric and patriarchal. A paradigm that excluded all those political, social, feminist excesses that nourished cultural production but disturbed the modernist ‘fairy tale’ of neutrality, impartiality and autonomy. Feminist criticism is already cultural criticism, as Nelly Richard states in the extraordinary text, among the first ones, we published. It aims to deconstruct the concatenation of signs, words, gestures and images of the ideological-discursive (patriarchal) structures through which culture produces knowledge, in order to challenge them. Hot Potatoes intends to propose undomesticated viewpoints, along with a careful examination of art as the cutting edge of neo-liberalism and the rhetorics that have legitimised it: in order to challenge the dominant powers, it is necessary to develop a counter-hegemonic vision at the level of languages, images and imagery. Therefore, being independent provides a certain degree of freedom, but it is from feminist critique that we learnt how to ‘stick in the throat of patriarchy’.

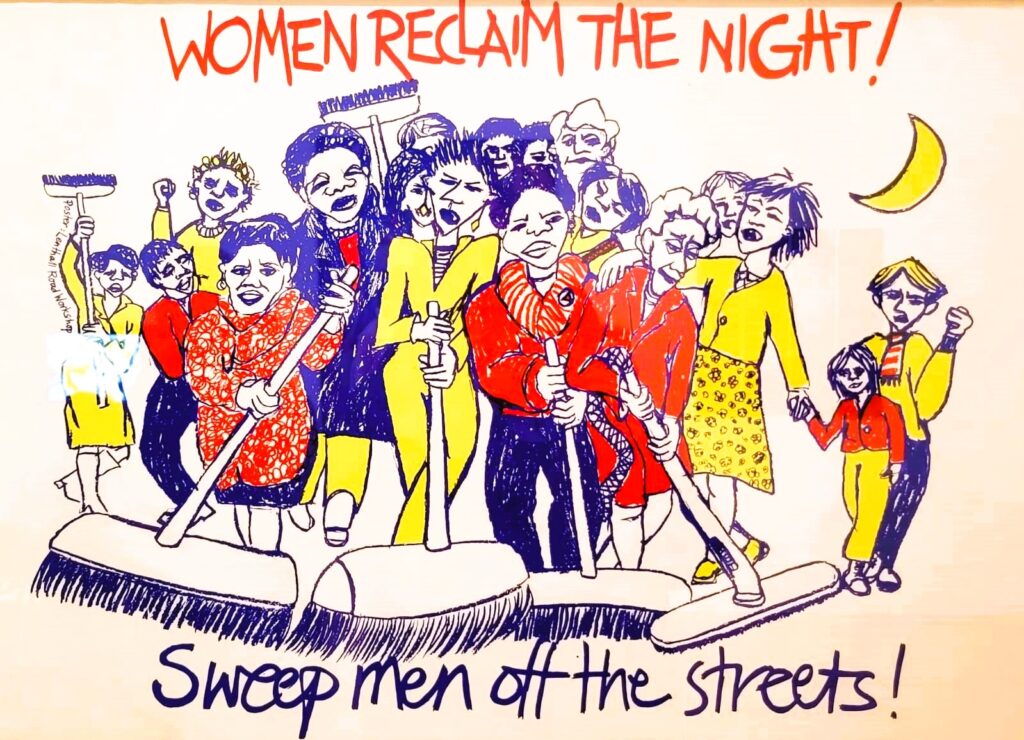

Lenthall Road Workshop, Sweep Men off the Street, 1980. Photo by Elvira Vannini

What are the most de-colonial methodologies in the museum system today?

There have been artists who have challenged institutions from within. But what does it mean to decolonise the exhibition space? Art is a cultural and aesthetic category that continues to be defined as white, masculine, western and bourgeois despite the many processes of inclusion, integration and institutional repair to which we have subjected it. Exhibitions remain exhibitions and do not change social hierarchies. Cultural policies focused on the rhetoric of difference and multiculturalism have not weakened systemic racism, except through aesthetic and façade operations. Museums remain normative places that correspond to a still colonial taxonomy;. There has been no revolution – only art washing operations – and I do not even know how this can be compatible with the museum order itself. A fundamental task is political work on archives in an attempt to rehabilitate and rewrite those histories that have been removed, buried, erased or otherwise concealed within the dominant historiographical design. Decolonising the structures of knowledge means deconstructing not only museums and exhibition sites, but also culture and the university. I like to think of the possibilities of ‘hacking the academy’. Operating in decoloniality means questioning, dismantling and destroying the old paradigms with which reality has been read.

Dora García, Si Pudiera Desear Algo (If I Could Wish for Something), video, 2021. Courtesy the artist. Photo by Elvira Vannini

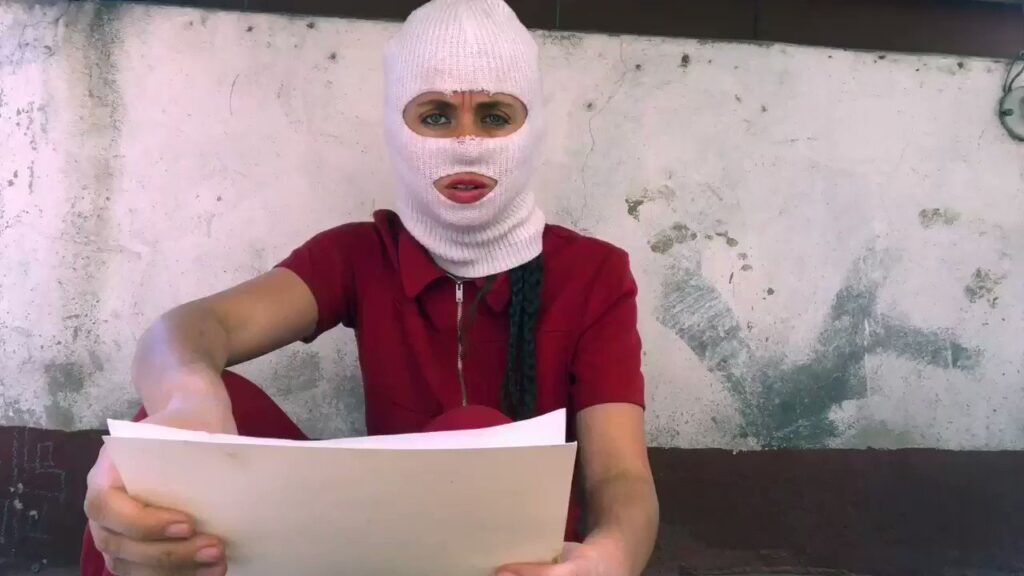

LASTESIS x Pussy Riot, MANIFESTO AGAINST POLICE VIOLENCE, 2020. Photo by Elvira Vannini

Talking about Italy, what is happening in the Italian art system?

If, as Audre Lorde said, ‘You cannot destroy the master’s house with the master’s tools’, neither can you accept the existing one or you can rebuild it in the same way, with the same conventions and cultural formats of modernity that we have inherited and never radically challenged. Definitely, in the Italian contex, the most problematic issue is the almost total lack of a space for criticism, as much as the absence of a counterpart. There is no antagonism, no dissident voice at the level of art journalism with regards to power structures. It is difficult to read interventions that denounce or point out all the questionable, often concealed, aspects of the structures of exhibition making or of the management of cultural and museum policies. If we think about the fact that the strongest and most politically centred attack around recent political events – starting with the ex-Minister of Culture Gennaro San Giuliano and the later Alessandro Giuli, to the controversial and embarrassing exhibition on Futurism – came from the investigative journalism of a television programme such as Report[1], rather than from trade magazines, it says a lot. Except for the few who stand out from the crowd, fearless of political confrontation, such as Tomaso Montanari, for whom ‘saying they are fascists is an intellectual duty’, in the rest of the art sector, where is critical thinking?

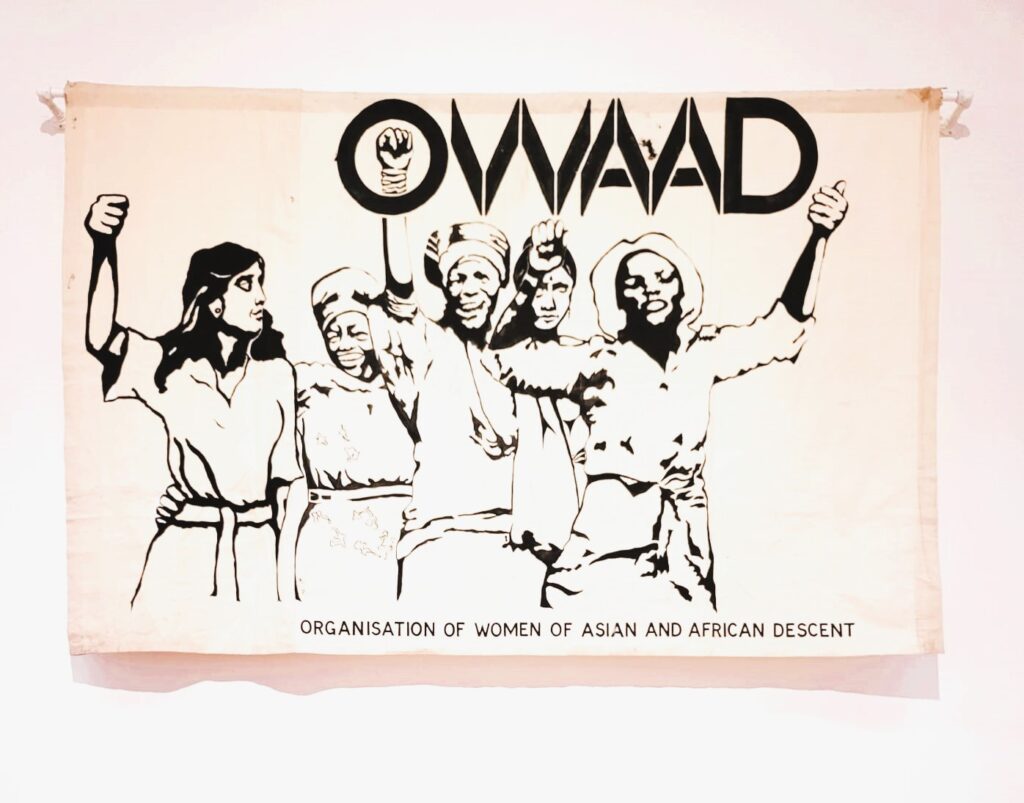

Banner di OWAAD – Organization of Women African and Asian Descent, dipinto da Stella Dadzie, 1978. Photo by Elvira Vannini

Talking about Museum of Civilisations in Rome and Mudec Milan, has there been any improvement or deterioration?

I have not yet visited the Museum of Civilisations in Rome although I have followed the events and the exhibitions they have rearranged with part of the collection closely. The approach announces itself as de-colonial but is colonised by the economic subservience of the strong powers of the art system, which is now reduced to the circuit of commercial galleries and only responds to its neoliberal and capitalist governance. To constitute a decolonial discourse, one would have to resist the reproduction of colonial taxonomies and not simply make an inclusive move, but reject the assumptions with which the exhibition culture of modernity has been erected. This also applies to Mudec and not only to ethnographic museums. I am thinking of a famous performance by the African-American artist Lorraine O’Grady who died a few days ago, who in the annual African-American Day Parade in Harlem, organised a performance ‘Art is…’, a golden float with a huge frame frames the street while a score of racialised performers march, dance and frame the audience of the Black community participating in the parade. As Françoise Vergès wrote in her forthcoming text The Museum as a Battlefield (Geoarchivi, Meltemi, 2025): The model is black, the frame is white. Here the problem is that we still cannot think of art outside that neo-colonial and modernist frame, outside that institutional context, inside the heart of the white colonial empire, which are our museums and exhibition systems.

Lorraine O’Grady, Art is…, performance, 1983-2009. Photo by Elvira Vannini

How would you like to conclude this interview?

We are steeped in colonial modernity and all its nefariousness, like the gherkins in the pickled jar that Rachele Borghi tells us about, an effective metaphor with which I would like to conclude the interview. The gherkins are immersed in a strong-tasting brine. The water is soaked with the combination of the ingredients of modernity: violence, racism, imperialism, capitalism and colonialism. It is not enough to take out a pickle and rinse it off to wash away that taste, for it is strongly impregnated with it. It is as if the paradigm of post-colonialism made it possible to see the world from a different point of view than the Eurocentric one, reversing the gaze (but not the sovereignty) forgetting that the world does not change so easily. Decoloniality, argues Borghi, does not aim to replace one paradigm with another, one discipline with another, but to destroy paradigms. Or in the words of Alpha Oumar Konaré, former president of Mali and of ICOM (International Council of Museums), in 1992 to the question: ‘How do we heal the colonial wound?’, he replied: ‘We must destroy the museum’. The museum is an expression of that kind of culture, our culture. One cannot, therefore, think of healing this wound with the mere return of works from the collections, or with the trap of inclusion and the rhetoric of multiculturalism. In my opinion, the function of institutions, research and criticism must be emancipated. To intervene in the rewriting of history, to break the centrality of heteronormative and racist narratives, to do political work on archives and direct criticism against power, to give voice to those disobedient, queer, non-normative, racialised bodies that do not exist in official documents, because silence produces invisibility.

Elvira Vannini is an art historian and critic. PhD in History of Contemporary Art at the University of Bologna, graduated from the School of Specialization in Art History. She has held seminars and lectures in numerous institutions, universities and academies, including IULM, 2011-12, Master in Gender Studies and Policies, RomaTre, 2020. Since 2010 he has been a lecturer at NABA, the New Academy of Fine Arts in Milan. He has published essays and articles both in trade magazines and on platforms related to the realities of the movement including Machina (DeriveApprodi), OperaViva Magazine, Alfabeta2, Commonware. She was co-host of a radio space on Radio Cape Town – Popular Network. In 2017 she founded the blog/magazine Hot Potatoes dedicated to the relationships between art, gender and politics through, from a feminist perspective. He currently curates the Dirty cube section for Machina magazine. She has published the anthology Femminismi contro. Pratiche artistiche e cartografie di genere, for Meltemi’s Geoarchivi series, 2023.